"Forgotten", "Left behind", "Written off" - Schools and the white working class (Part 2)

The second post in this three-part series suggests five actionable strategies that could begin to address underachievement in schools by white working-class children.

My previous post dealt with the opportunity presented by the Independent Inquiry into White Working Class Educational Outcomes commissioned by Star Academies Trust. (The naming is diplomatic: the inquiry will focus on white working-class underachievement.)

I concluded that there was both a political imperative for change, related to the populist wildfire sweeping white working-class communities in Britain, and an opportunity brought about by the expertise of the commissioners themselves, many of whom enjoy greater ongoing involvement in working class communities than was the case in previous bodies tasked with looking into this topic.

This post includes five initiatives that could contribute to positive change. I make no pretentions to originality or to comprehensiveness—that will have to await the Committee’s more considered recommendations in late 2026. My suggestions borrow liberally but deliberately from previous inquiries, in addition to being rooted in my own experience. Not all these initiatives can be implemented without a cost to the public purse—a serious constraint in straightened times—but all could be implemented without fundamentally disrupting the schooling system. These initiatives also align with the Labour government’s stated ‘missions’, other objectives, and, where possible, existing policy initiatives.

None of these initiatives is a quick fix and none should be considered a solution entire. I am focused professionally on what can be achieved within the education system, but I don’t want to leave the impression that this is a task for the education system alone. Disjointed policy-making that sought to separate education from health, social care, and other services is one reason why government has largely failed this group of children the past two decades.

So framed, my five initiatives are:

1. Expand Better Futures on the Sure Start model

2. Improve poorer kids’ access to the best schools

3. Raise the quality of teaching in affected communities

4. Reward aspirational curriculum design for poorer students

5. Extend the Pupil Premium to age 18

Each initiative is described in summary below.

The third post in this series explores measures that come into view if we widen our aperture of inquiry by suspending considerations of cost, vested interests, or near-term institutional capacity.

1. Expand Better Futures on the Sure Start model

Virtually every serious review of white working-class educational outcomes in the past decade-and-a-half has lamented the demise of the Sure Start programme from 2010 onwards. Sure Start, introduced by New Labour in 1998, created community hubs offering a flexible combination of childcare, early years education, parenting support and family outreach, health services and links to training and employment support for parents. By 2010, there were over 3,600 Sure Start centres across the country, many contributing directly to improved educational and health outcomes, greater family stability and improving community cohesion.

Three design features contributed to the programme’s success. Sure Start’s focus on early intervention was a textbook case of public policy preventing rather than responding to negative social outcomes. The combination in one place of services from across local government enabled holistic forms of support for under-resourced families who often found navigating local government bureaucracy challenging. And allowing flexibility in the exact mix of services allowed the programme to be responsive to local need.

The programme was not perfect. Failing to ring-fence funding for Sure Start meant that, when local government began to feel the effects of “swingeing cuts” in the early 2010s, many councils chose to pare back services directed towards low propensity voters, i.e. the poor, rather than those that were more politically engaged. Alignment between schools and other local government services was never perfect—as evidenced by Ed Balls’ short-lived attempt to reintegrate schools into children’s services through his 2008 Family Hubs initiative. The price of local decision-making was, as always, inconsistency in implementation. Some councils simply did a better job than others with Sure Start.

None of these is a reason to abandon the lessons learned from Sure Start. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ recently-announced £500 million Better Futures Fund provides, in principle, a route back into this space, albeit via civil society organisations rather than local government.1 Over time, an expanded Fund might provide funding for locally-integrated services that could increase working class communities’ resilience and their connectivity to the schooling system. The Child Poverty Action Plan launched in July by the North East Combined Authority is an example of what could be achieved elsewhere.

There is a mantra that public services meant only for the poor are fated to become poor public services. There may be something to this point, but it grates against the reality that Britain is very far from the levels of social cohesion that would facilitate a Scandinavian-style combination of higher marginal taxation with efficient public services.

2. Improve poorer kids’ access to the best schools

Poorer students are less likely than their peers to attend the highest performing schools. Analysis by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) on behalf of the Sutton Trust has repeatedly shown that top performing secondary schools in England have materially lower rates of FSM-eligibility among their students than the average school. Three quarters of these schools admit fewer such pupils than are represented in their local area. Grammar schools, excluded from the NFER analysis, tend to be in more affluent areas of the country. Even so, they educate fewer FSM-eligible students than are present in their local communities.

The under-representation of poorer students in higher performing schools contribute to the obstinate association of poverty and poor grades in popular discourse. On this reading—which extends well into the schooling system itself—schools are simply social sorting hats that place children into attainment buckets already pre-destined by their background. We should not tolerate this view.

One way of improving working class kids’ access to quality schooling would be to amend the Schools Admissions Code to make all schools include eligibility for free school meals in their oversubscription criteria.2 The government could reasonably point to its recent decision to widen eligibility for free school meals to all households receiving Universal Credit as the basis for such a change, and as part of a strategy to combat a broader spectrum of disadvantage. (This would be a significant win, given that the number of students that will actually benefit from the change in elegibility requirements is, to say the least, disputed.)

Schools and local authorities would retain significant freedom to set their own admissions criteria but would gain an additional duty to a clearly-identifiable vulnerable group—sitting behind existing duties to children in care and (currently) those with Educational Healthcare Plans. This would ensure that all schools were shouldering some measure of responsibility for combating educational inequality.

The reformed system would still be far from perfect. Disadvantage is a slope rather than a step. Some—clearly, not all—grammar schools would likely resist rapid change by amending their academic entrance criteria to reinforce the virtual monopoly on places afforded to middle class households. But a principle of inclusion would be established that, over time, could translate into a fairer reality. A change in the code would also potentially stimulate positive middle-class engagement with the second and third preference schools that would now be more likely to educate their children. This seems consonant with the government’s attempts to wean—or to flay, depending on your perspective—professional families away from the independent sector.

Put another way, how can we claim a sincere national effort to combat disadvantage without recognising disadvantage in the Schools Admissions Code?

3. Raise the quality of teaching in affected communities

Diplomacy should not become mendacity. If around one third of the children in Britain—roughly the percentage that identify as white working class—are to do better in school, many of the schools they attend will need to be more effective.3 The British schooling system has never adequately learned the lessons of the rapid improvement in educational outcomes that took place in London in the early years of this century. The central lesson of this experience is that effective provision matters enormously, even if it does not matter exclusively.

As Tony McAleavy and Alex Elwick of the Education Development Trust concluded their review of school improvement in London:

“the improved performance of London schools [between 2005 and 2013] could not easily be explained in terms of external factors such as ethnicity or resources ... [T]he internal effectiveness of schools had changed for the better.”

Among the key changes McAleavy and Elwick identified as contributing to increased school effectiveness were the coordinated framework for school improvement provided by the London Challenge and Teach First, which brough well-qualified and committed graduates into more complex urban schools in large numbers.4

Sceptics about the transferability of these measures have pointed to a ‘London effect’. Britain is one of the most metropolitan societies in the world. The capital obviously enjoys advantages over other cities that contribute to the success of its schools. Three advantages receive the most airplay. First, London is an opportunity hub; students are easier to motivate when they can see, and easily visit, excellent universities and employers. Second, the aspirational nature of London’s large first- and second-generation immigrant population means that those teachers are dealing with a population that is more receptive to education than many white working-class communities. Third, London is a preferred destination for young professionals, teachers included, at the early stages of their career; they bring a wealth of hard graft and dynamism to schools.

I have sympathy with each of these points, but each is more complicated than it first appears. Anyone who has taught in Inner London knows that children’s practical experience of the capital is often tightly circumscribed by family means, insecurity and concerns about violent crime. I taught for three years in a school in Brixton where more than eight in 10 students received free meals. Most children had never seen the Thames (three kilometres away) and many claimed, plausibly, never to have left their housing estate. That experience is not atypical. Psychologically, Surrey remains closer than Stepney to the City of London.

As far as the argument about “immigrant energy” is concerned, it should not be surprising that parents who have uprooted themselves and moved to another country in search of a better life for their children expect those children to make the most of the opportunity. But this is not easily dismissed by an appeal to amorphous notions of ‘culture’ or ‘national character’. Professor Steve Strand demonstrated almost a decade ago that differing parental behaviours among those communities were key to understanding the difference in ethnic groups’ performance in schools. Those behaviours are replicable—with sufficient support.

The third advantage, the relative ease of teacher recruitment, has clearly eroded over time. Twentysomething teachers are no longer habitués of London bars, restaurants, coffee shops and cultural venues; most struggle to meet the soaring cost of housing in the capital. The presence of excellent teacher training institutions remains a modest advantage, as does the relative abundance of mission-driven schools promising relatively rapid career growth. Still, I am not the only Head serving in London who finds that the main reason for losing teaching staff is colleagues’ need to relocate to afford a decent standard of living.

Nonetheless, we need better incentives for teacher recruitment in and relocation to educational ‘cold spots’, many of which have large white working-class communities. These incentives need to apply to teachers at all stages of their career, rather than being focused on new entrants to the profession—those bright graduates that Teach First funnelled into London schools were trained and supervised by more experienced colleagues who generally receive less of the credit than they deserve. Enhanced incentives also need to apply to colleagues in leadership roles. High performing teachers will not stay long in under-performing schools.5

We need a properly funded national pay scale that reflects the realities of recruitment and retention alongside cost-of-living factors in different communities. There is no reason, other than a misconceived sense of equity, why colleagues teaching in the most challenging contexts should not be paid more for doing so. We have relied for too long on the wholly unevidenced idea that teachers’ emotional investment in specific communities will power student achievement more surely than characteristics, such as their level of qualification, that have a clearer market value. This has been to students’ detriment. The current government’s initiative to establish a “floor but not a ceiling” on teachers’ pay provides an important first step in designing proper incentives for the most effective teachers to go where the need is greatest.

4. Reward aspirational curriculum design for poorer students

Like our prime minister, I too am a pragmatist. I supported the introduction of the Ebacc in 2010 for several reasons—most importantly as a good faith attempt to promote a curriculum that would give students from all backgrounds the widest range of opportunities at age 16. As the 2011 Wolf Review demonstrated, schools had become too reliant on delivering qualifications that had little currency either in higher education or the jobs market. The Ebacc seemed like a reasonable corrective.

More than a decade on, however, the Ebacc has clearly failed to deliver on its promise. In part, this is because there has never been an honest reckoning with the resourcing required to deliver the Ebacc successfully. The supply of highly qualified science and languages teachers, for example, has never approximated the demand for them nationally. And the incentive structure in the teaching profession enabled schools in more affluent areas, or those in the independent sector, to harvest a disproportionate share of those teachers (see above). There is also something to the argument that elements of the Ebacc were always more accessible to more middle class children with access to university-educated parents and a greater stock of learning resources in the home.

Developments in the economy and in wider society have likewise moved against the Ebacc-for-all model. In post 16 education, STEM-related courses have raced away in popularity while those in the humanities and languages have stalled, if not gone into reverse—a consequence of society’s rising need for computational skills and the perception that STEM courses and degrees offer greater prospects for employability. This development has, in turn, sapped prestige and urgency from shrinking subjects in schools. It cannot be known whether the impact of AI will change this picture in the near term.

We need a framework for curriculum development that combines a robust foundational element—made up, perhaps, of a renewed national curriculum at Key Stage 3 and including a redoubled commitment to securing strong passes for all students in English, mathematics and science at GCSE—but which allows schools to offer qualifications that are sensitive to their local context, including local employment opportunities. The government’s National Curriculum Review may provide the former; the “MBacc” being developed by the Labour-led metropolitan mayoralty suggests a model for the latter. A more robust role for Ofqual would be required to guard against another proliferation of low-quality qualifications.

5. Extend the Pupil Premium to age 18

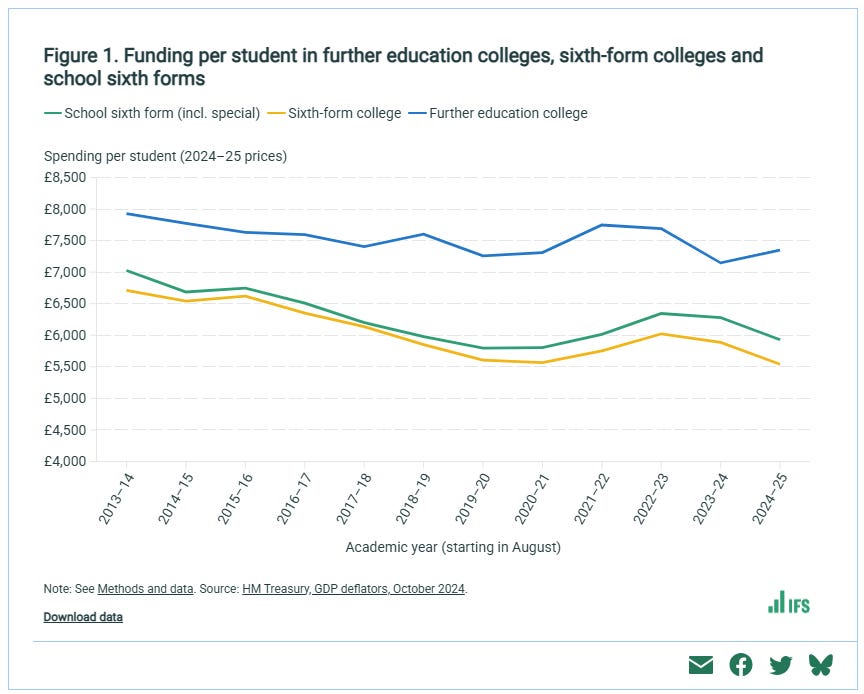

Funding for post-16 education has been savaged in the past 15 years. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that colleges lost around 13% of funding per pupil between 2010 and 2025, while school sixth forms lost almost twice as much. Despite the school leaving age having been raised to 18 in 2015, subsequent governments have continued to treat post-16 schooling as an afterthought, or as somehow structurally cheaper-to-deliver than other phases of education. Contrast this with the prevailing tendency in the independent sector to increase resources committed to young people’s education during these vitals years of preparation for university, apprenticeships or employment.

The most egregious feature of the underfunding of older students’ education is the absence of ring-fenced resources to combat the impact of household poverty. The Pupil Premium Grant, since 2011 the funding stream most directly targeted at combating disadvantage, stops at age 16—a tacit, but absurd, conclusion by all major parties that 17- and 18-year-olds in full-time education face no additional challenges if they happen to come from poorer homes. Presumably, no government minister has ever met a sixth former whose choice of school or college was constrained by the cost of public transport; or who bore caring responsibilities for a younger sibling or disabled parent; or who was made homeless during their education. I would be happy to facilitate introductions.

I don’t believe that teachers and school leaders exhibit reflex responses to public policy incentives. But are we really comfortable with a school funding model that judges schools based on outcomes while denying them the resources properly to educate the most vulnerable groups, those whose learning is most recursive, whose families have the least experience of continuing education? Could this not be interpreted as a dog whistle to keep these groups out of our academic pathways, if not out of school altogether? Shouldn’t we oppose this situation in principle, even if combating inter-generational poverty were not a public policy priority?

We urgently need to extend the Pupil Premium to the final phase of secondary education, to reflect both the realities of a raised school leaving age and to provide schools with resourcing properly to support vulnerable learners. An extension of the grant would speak directly to Bridget Phillipson’s committment to supporting ‘left behind’ communities. We must build accountability frameworks for schools that encourage local initiative, but ensures that additional funding directly reaches those students it is meant to support—rather than being used as financial ‘Polyfilla’ to repair cracks left behind by a decline in core funding and rising costs. Such a change in policy would not fully meet the overall challenge of school funding, still less close the now caverous gap between state and independent school per pupil funding rates, but it would be a step towards equity in state-funded education and a vital statement of support for working class communities.

I appreciate that some readers may have strong views about the proper role for local government in all such matters. I am frankly less concerned with the responsible body than with its effectiveness.

As opposed, for example, to proposals for lottery-based admissions, which seem a particularly blunt tool and one that corrodes both academy and local authorities’ prerogatives when it comes to admissions. I should disclose here that my own school includes exactly this priority for FSM-eligible students in its admissions policy.

To be clear, I am in no way suggesting that this is true in every case or denying the existence of some exceptional schools serving disadvantaged communities.

To disclose an interest here, my sometime co-author, Ian Warwick, played a prominent role in the London Challenge.

Nick Clegg proposed something similar in 2013 when he suggested a scheme for incentivising senior leaders with proven track records to relocate to coastal town and parts of the country affected by de-industrialisation. The initiative fizzled out because of a lack of proper planning and little to no evident funding. It was not helped by being badged, embarrassingly, as a ‘Champions League’ of Headteachers.