How should we think about the 'engagement crisis'?

Persistent absenteeism says something important about schools, but not only about schools.

Britain’s schools are suffering from an “engagement crisis”, Becks Boomer-Clark, chief executive of Lift Schools, told the Lords Social Mobility Policy Committee earlier this month. “We’ve got a more discerning group of young people who are telling us … that what we’re offering many of them day-in-day-out in school, does not match their needs … [is] not relevant to where they are or what their future aspirations are,” she told Lords.

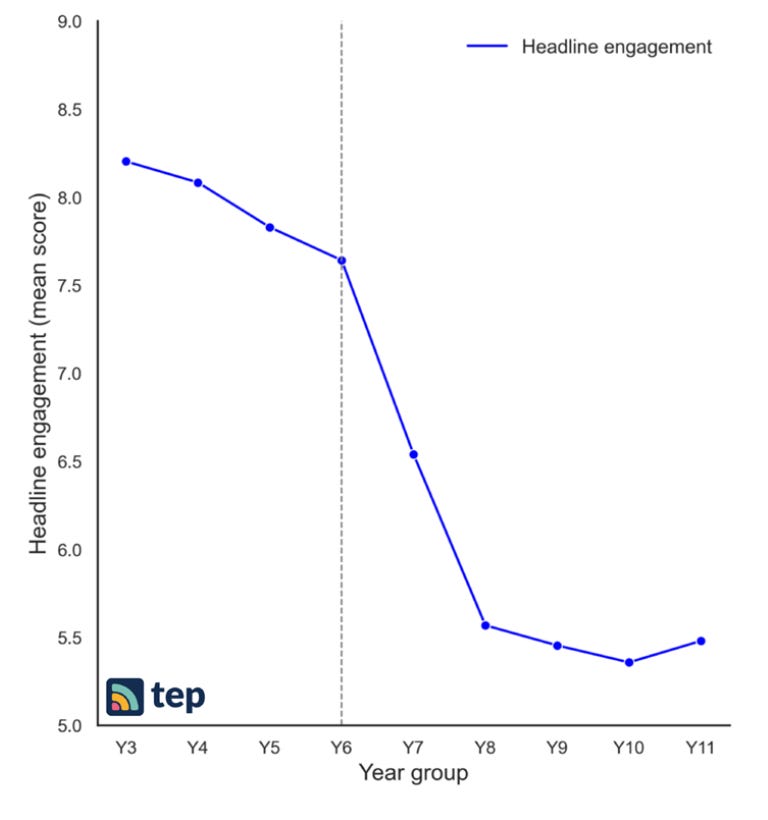

Boomer-Clark’s comments amplify the recent conclusions of a study by the ImpactEd Group and others. The study found that fully a quarter of pupils in England experiences a “steep and lasting” drop in engagement when they move up to secondary school. The research tracked how pupil engagement changed across the 2024–25 academic year and found pupils’ average school enjoyment score virtually halved between year 6 and year 8. A sense of safety fell by almost 20 percent among girls and by around 11 percent among boys. Neither figure recovers much before year 11 (see below).

Graph 1: Headline engagement in English schools by year group (ImpactEd analysis)

Grim reading, but not altogether surprising. A dip in progress during Key Stage 3 has been a recognised deficit of British schooling for some time. A decade ago, Ofsted branded these ‘The Wasted Years?’—the question mark reflecting politeness on the part of the report’s authors rather than any ambiguity in its findings.

So, what has changed? The answer is that disengaged students have stopped attending school in terrifyingly large numbers. The latest government figures, published in March, revealed that the number of pupils classed as “severely absent” in England plateaued at or around a record high last year. The percentage of students missing more than one in every 10 schooling sessions, remains almost twice as high as it was pre-pandemic.

The ImpactEd study says absenteeism is linked to—it properly avoids the phrase ‘caused by’— lower levels of engagement. ImpactEd concludes that the top 25 percent most engaged secondary pupils are 10 percentage points less likely to be persistently absent than those in the bottom 25 percent.

Engagement is trending

The topic of engagement is perennially essential to education. It is also trending, thanks to the positive reception accorded to Rebecca Winthrop and Jenny Anderson’s bestselling book The Disengaged Teen: Helping Kids to Learn Better, Live Better and Feel Better. Winthrop and Anderson draw on a global study of over 65,000 students conducted by the Brookings’ Institution, where Winthrop directs the Centre for Universal Education.1 The same study underpins ImpactEd’s work.

The net takeaway from both studies is that disengagement in early adolescence is a virtually universal phenomenon, but, according to Professor John Jerrim, lead author of the ImpactEd study, the situation is “more pronounced” in the UK and more correlated with social class. Students from under-resourced homes are substantially more likely to experience disengagement, if not disillusionment, in the early stages of secondary school.

The demographic dimension to the analysis is telling—and highlights why we should be cautious in following Time’s Arrow backward from absenteeism to disengagement to apparent curriculum redundancy.

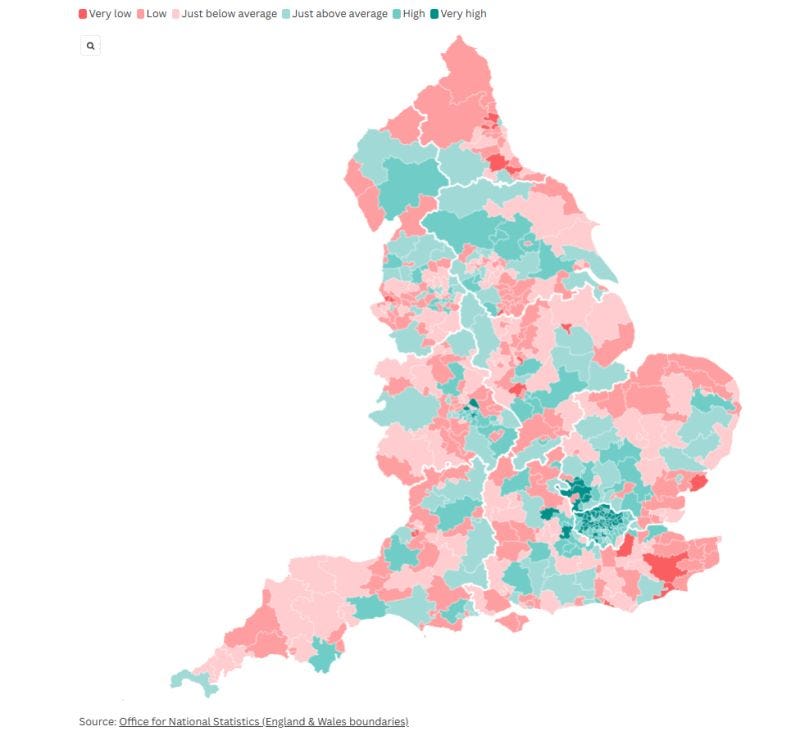

School absenteeism is at its most severe in ‘Left Behind’ areas of the country characterised by high levels of absolute poverty, food poverty and child poverty, chronic health inequalities, rising homelessness, fraying social infrastructure, low rates of civic participation and, more recently, high levels of support for Reform UK. These are also the parts of England with the lowest rates of social mobility, as analysis by The Sutton Trust has demonstrated. And this is all before we consider the negative impact of social media on adolescent attention spans—an increasingly well understood phenomenon that seems negatively correlated with household income.

So, a suite of obstacles to active engagement with school, a growing sense of poorer families’ alienation from public institutions, and a feedback loop that casts serious doubt on the link between working hard in school and enjoying a better, more prosperous adulthood—small wonder that absenteeism is proving so intractable.

Graph 2: Sutton Trust Opportunity Index: Social Mobility by Region/Constituency

What is missing is a strategy for wrap-around support for young people in these areas, with schooling at its heart. Something like this was (briefly) envisioned by then Education Secretary Ed Balls in 2008, when he introduced legislation requiring schools to participate alongside other public services in Children’s Trusts that would develop joined-up plans for children and adolescents.

Unfortunately, the strategy did not have time to embed or to show results. Its revival is doubtful, given that the public services required to work alongside schools have since been fileted by almost two decades of cuts and are likely to lose out further in Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s Spending Review.

What can schools do?

This does not, of course, mean that schools are wholly impotent or that they should not reflect critically on existing practice, including the school curriculum. The interim report by the Curriculum and Assessment Review Panel is almost certainly too sanguine in concluding that the key stage system overall is “broadly working well”, offering the caveat that too many schools gave over valuable time in years 7 to 9 either repeating topics well covered during primary years or ‘front-loading’ GCSE content. This reads as motivated reasoning, considering the ImpactEd analysis.2

One object of critical reflection must be the instrumentalization of education that takes place around secondary transition. Broad generalisations may be unfair, but it is truer than not that primary schools have held firm to the sense of education as something that is inherently valuable and life-affirming while secondaries have stressed the future market value of learning as their preferred way of motivating students. This is a bigger topic than I can fully explore here, but it seems unsurprising that children should prefer a system that promotes wonder and celebrates current achievement in its own terms over one that sees both as little more than routes to a better-paying job.

Boomer-Clark told the Lords that children today have “much greater awareness of what the world’s probably going to look like”. I think it would be more accurate to say that children today recognise more clearly the limits of their teachers’ future-sense. How can you promise future rewards if you cannot predict the future? The pace of technological and social change defies educators’ vision because it defies everyone’s.

Would secondary schools re-dedicated to the value of education as an absolute social good fully defuse the combinatorial explosion of factors leading to record school absenteeism? That is likely to require, in Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson’s words “hard graft” well beyond the schooling system. But it is a place to start.

I will return to this work in a future post.

A more generous interpretation would be that the Panel recognises that structural reform of the education system, shaking up the key stages, is all-but impossible given the state of public finances. Nonetheless, it is worth considering that the existing separation of primary and secondary schools dates from the 1902 Education Act and, even then, reflected a pragmatic compromise with the status quo ante rather than a philosophical or scientific conviction that 11 was the ‘right’ age for such transition. The Independent Schools Sector retains progression at 14 as the norm, as do some outlying Local Authorities in England.